Ergo das Ego

Dale Webster on the Windows to our Soul

I am a painter of people and I suppose that the purpose of the pictures I make is to explore what and who we are, that particular awareness of another person, or myself, through the representation of a look seen in a face. Sometimes they work, and I can see that person in the picture in front of me, as if we were sharing our thoughts. How this is achieved is not always clear, but sometimes it is simply technical, like the manipulation of the light in the eyes.

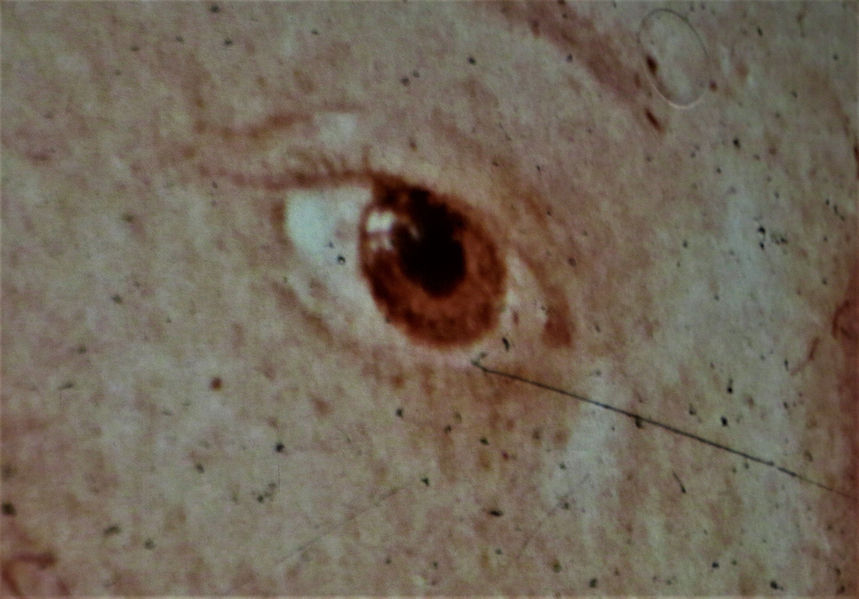

Some years ago, when I was lecturing in Art History, I took a slide-making trip around some of the smaller galleries in Germany. In one of them, I came across the portrait of a young girl wearing a red beret, a small picture of a distracted girl, in simple German dress, painted in 1507. I cannot recall the gallery. I lost the record, but the painting’s provenance is Berlin, so it was probably on loan. I took a slide, using slide film in those days, and used it in a lecture to reinforce a point I was making about Durer’s use of a window in the eye highlight, as in his Self Portrait of 1500.

This was a device I think invented by Durer to reflect the light source in a studio or internal space. He did in fact use the same device in external as well as internal portraits. It became ubiquitous. The eye-light to give life to the subject goes way back, first used, on the Egyptian Fayum mummy portraits two thousand years ago, to show life in transition to death. The wonderful realist portraits showed their appearance in life, and the eyelight capturing the person they were.

When Durer's image was enlarged in projection, sure enough, there was the window highlight, but also, we can see a figure silhouetted in front of the window which seems to be holding something in the left hand, a brush perhaps. Durer was, by all accounts left-handed. So, this figure standing in front of the light source and reflected in the girl’s eye is surely the figure of the painter himself. The eyelight is of course incredibly tiny in this small painting but blown up on photographic film, there it was, and seen by all present. It can’t be seen in digital images, only on film, because of the digitised pixilation.

What I wanted to explore, as with so much art historical research was, why the picture was made, and made in this way. It is unusual for the subject of an oil painted portrait of this period to be so simply dressed and not showing off the wealth, property, or the obvious attractiveness of the subject. She is shy, looking away, deep in thought and blushing. It would seem therefore that this was not a commission. But here was an explanation. He had put himself into the eye, and hence by allusion, into the thoughts of this girl, and so her demur internal gaze was directed at him. He has shown a subject who is seemingly thinking loving thoughts about him. Hence, we can conclude that he painted it for himself. Of course, most of us now keep pictures of those we love, or as in this case, of those who love us.

This picture is likely to be an early example, and it is a wonderful example both of Durer’s skill, and his reputed ego. His self-portrait really does resemble a traditional renaissance image of Christ the redeemer. The eyelight has of course huge significance in understanding how a person can be shown in an image, whether painted or photographic. It is used ad nauseam by advertisers to attract us to products presented by pretty people, but none I think have the wonderful complexity of Durer’s Face of a Young Girl in a Red Beret.

Dale Webster is a retired lecturer in Philosophy and Art History, and latterly, a painter of portraits in Kenya and the UK. dalewebster.carbonmade.com